One of the biggest challenges a coach or player faces is making a physical game change. Over time, all repetitions have led to a more automated execution, whether these movements are biomechanically efficient or not. Specifically, physical movements become increasingly automated to preserve brainpower efficiency and to increase the speed at which an individual executes a movement. In short, practice literally makes permanent.

To illustrate, magnetic resonance images (MRI) of golfers’ brains revealed significant differences between experienced players and beginners in regard to which part of their brain was active during a swing. For beginners, the basal ganglia and limbic system were both very active. These regions of the brain are involved in emotional response (stress and fear) as well as conscious awareness of physical movement.

“Practice may not make perfect, but it makes permanent.”

—John Milton (in Bascom, 2012)“Practice can actually change the physical wiring of the brain to support exceptional performance.”

—Beilock, 2010

In this month’s Slowinski at Large, I discuss an error correction technique that has been demonstrated to help elite athletes make changes to physical execution quickly and effectively. Finally, I present my own case study of implementing this error correction process and the results obtained with one of my bowlers who is preparing for the European Championships in August.

Old Way / New Way method of error correction

The Old Way / New Way is a structured process to alter an athlete’s current physical movement areas of weakness leading to more preferable actions. Specifically, it involves a cognitive reflection and awareness development process which strives to alter current action by proactively interfering with prior knowledge and facilitating new learning.

The process was created by Lyndon (1989) who was studying ways to improve learning in special needs students and developed the Old Way / New Way process. It was soon adapted by coaches and sport psychologists to improve athlete performance at the Olympic level and has had a significant impact on changing performance quality.

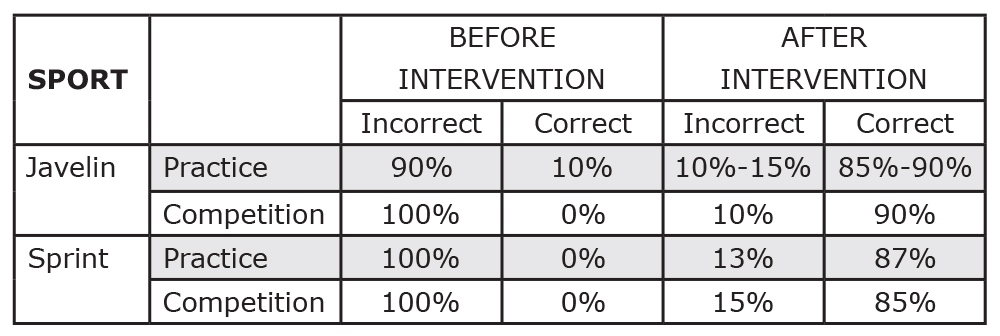

Table 1. Correct execution in an Olympic javelin thrower and an Olympic sprinter. (Hanin, Y., Korjus, T., Jouste, P. & Baxter, P. (2002))

Here are the findings of implementing the Old Way / New Way model with Olympic athletes. Table 1 provides data of the percentage of correct physical execution before and after implementation for competitors in javelin and sprint events.

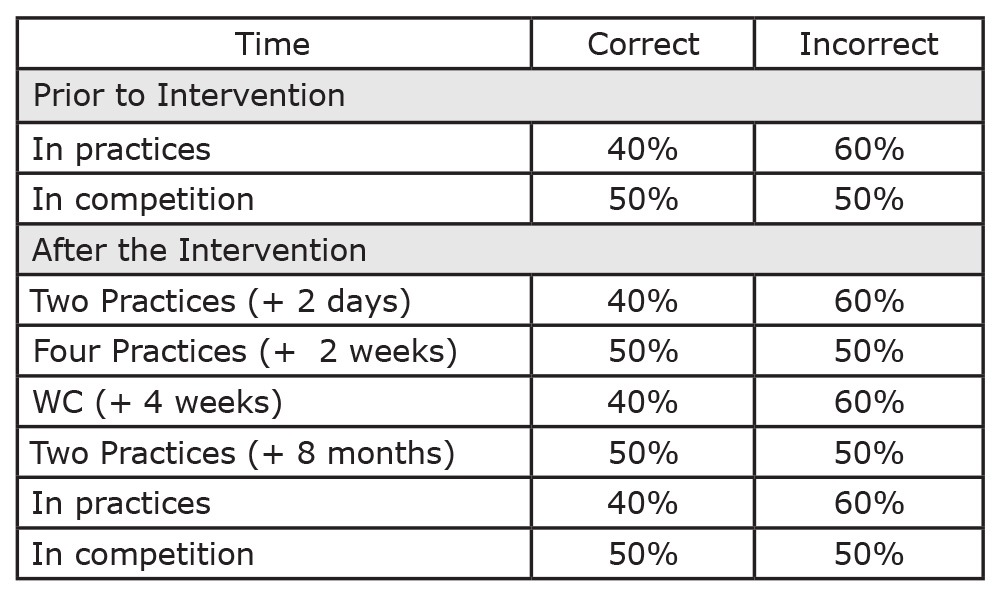

Table 2 refers to an Olympic swimmer. WC indicates the event is the World Championships. The “+” indicates the amount of time between the intervention and the competition.

Error correction technique

Here is a detailed overview of how to implement the error correction process as a coach or a player in an effort to modify a physical game element. I have utilized/adapted the process used with the Olympic athletes as discussed in Hanin et al (2002) and Hanin et al (2004).

Step #1: Collect data to determine frequency of incorrect technique

In an effort to justify a change and to provide baseline data to use during discussions, complete an assessment of the frequency of incorrect technique as a starting point. This should be completed for both incorrect technique in practice as well as incorrect technique in competition. Data collected in both environments will lead to a more productive conversation to alter the process.

Step #2: Describe the rationale for changing from the current execution to a new execution

A coach should conduct a thorough error analysis to initiate the process. Fundamentally, it is critical the bowler believe a change will improve their game and understand what current physical issues are limiting their performance. Data from Step # 1 will aid in this process.

Step #3: Develop awareness and describe the current execution

Awareness of physical execution is the only way an athlete can feel the difference between quality and poor implementation. Formally articulating physical feelings and sensations leads the bowler to become consciously aware of the current execution and begins the formal cognitive reflection process.

The coach observer should inform the bowler when an incorrect physical game movement is executed. Once an awareness of the sensations associated with the current execution, the bowler shoulder formally write down the specific feelings and sensations in their fingers, wrist, hand, forearm, shoulder, legs, and feet. For example, whatever they feel and wherever they feel it should be formally written down. Both the awareness development and formal writing process are essential in changing from the current to the new desired execution.

Step #4: Develop awareness and describe the new execution

After formalizing the feelings associated with the current physical game execution, the coach should aid the player in establishing the change. The coach observer will inform the player when proper technique is executed. Once the player has established awareness of the desired new physical game change, a formal written articulation of the feelings and sensation associated with the new execution should be completed.

Step #5: Compare the two executions by alternating between the two

Now that the player has developed awareness between the old and new physical game executions, there needs to be a formal comparison between the current and new by going back and forth between the two. Complete at least five sets of old and then new. As the bowler is migrating between the old and new, the player should write down the specific feeling and sensation differences when comparing the two.

Step #6: Implement the new execution

As a final step in the error correction process, the bowler should make an effort to only execute utilizing the new physical game.

Step #7: Data collection over time

As a final assessment, the coach should collect both practice and competition data to assess the frequency of correct technique.

Case study: Romanian national champion Romeo Gagenoiu

Since I first arrived in Romania, Romeo Gagenoiu and I have been working on improving his timing. Historically, he used a four-step approach, starting the ball into the swing on his second step. In an effort to improve timing and fluidity, I converted him to a five-step delivery, yet he would still start the ball late, on the third step. Consequently, Romeo was losing potential energy transfer due to excessive grip pressure throughout the entire swing and into release.

His follow through was under his head, yet the elbow didn’t remain inside or parallel with the wrist. The worst impact was frequently falling off at the foul line, especially in competition when the pressure was on him to make a shot. Before the intervention, his ball movement into the swing was 100 percent incorrect and he fell off shots over 50 percent of the time in competition.

Romeo recently won the Romanian National Championships but performed at a level that is unacceptable to both of us. We both know he is capable of a significantly better performance in the European Men’s Championships in August in Vienna. And, with this as the goal, we embarked on the Old Way / New Way extreme makeover process.

To begin the process, I explained to him that in order for him to compete in Vienna, we needed significantly better shotmaking and energy transfer from the body to the bowling ball. Currently, he could get to the pocket but wasn’t carrying at a level competitive for the European Championships. He is falling off too many shots during competition. This is leading to a loss of leverage at the line as well as preventing the accurate observation of ball motion and lane transition. As an added incentive to make a change, he will compete in the WTBA World Singles Championships in Cyprus as well as the European Champions Cup in the Netherlands.

We started with throwing shots to gain awareness of his physical sensation throughout the approach and release. I also took video to demonstrate the Old Way. After about ten shots, Romeo formally wrote down what he felt. His feelings included the following:

- I have a sense of late timing throughout the approach;

- I am squeezing the ball throughout the entire swing;

- My swing feels controlled;

- I have a feeling of excessive body tension; and

- My release is controlled due to the excessive grip pressure.

To move into the new and desired approach, I asked Romeo to focus on using the left foot as a trigger. When he felt the left foot compress on the ground, he should move his hand down and let the ball drop into the swing (keep the elbow close to his body). We also focused on keeping the elbow inside the wrist and under the head on the follow through. His cue words were “step + drop + elbow in.”

He was able to gain a feeling in approximately ten shots. The formal written thoughts of the New Way included:

- My timing is quicker;

- I am not squeezing the ball;

- My swing is free throughout the entire swing; and

- I am not thinking about the release since it is relaxed.

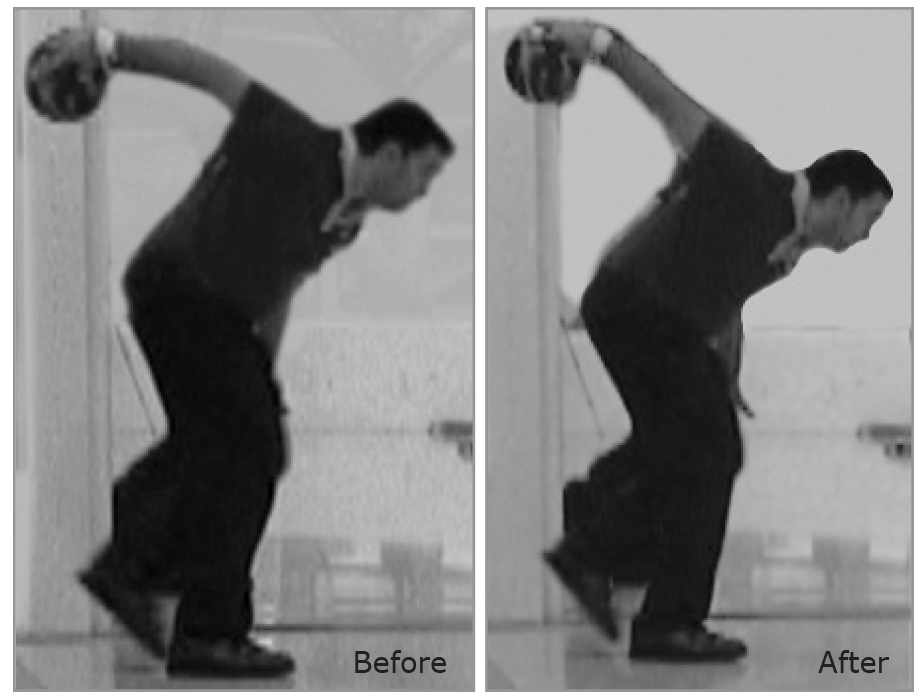

A video comparison of the Old and New approach was shown to Romeo after the formal writing process was complete. The visual findings included:

- Late timing especially at the top of the swing and good timing on the new;

- His hand position was to the outside of the ball on the old but on top of the ball in the new approach; and

- His arm was significantly straighter at the top of the swing on the new.

After he pointed out the differences and I discussed with him about the importance of the New in reaching our collective goals, he went back and forth on ten shots, noting the differences. After completion, he wrote down the differences again.Finally, I asked him to complete fifty shots with the New approach. He was successful in starting 76 percent of the time. He was able to naturally post 100 percent of the shots.

The ball motion, ball speed, and rev rate significantly improved. Since these changes, he has posted the majority of shots in competition and he won an open tournament after qualifying with 221 on the WTBA Seoul pattern and completing three rounds of match play.

Conclusion

The term muscle memory has been utilized to describe habitual and automated movement. Over time, the brain utilizes less conscious thought and motions become automatic based on the environment or triggers to do something. Consequently, bad habits can become ingrained and automated. The only way to alter these is to create awareness and implement a new learning process to establish a difference between the current and the desired new execution.

References

Ashby, F.G., Turner, B.O., & Horvitz, J.C. Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14(5): 208–215.

Beilock, S. (2010). Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal about Getting it Right When you have to. Free Press: New York

Bascom, N. (January 14th, 2012). Brainy Ballplayers: Elite athletes get their heads in the game. Science News 181 #1 (p. 22)

Hanin, Y., Korjus, T., Jouste, P. & Baxter, P. (2002). Rapid technique correction using Old Way/New Way: Two case studies with Olympic athletes. The Sport Psychologist (16) 79-99.

Hanin, Y., Malvela, M. & Hanina, M. (2004). Rapid correction of start technique in an Olympic-level swimmer—a case study using Old Way/New Way. Hanin, Y., Malvela, M., &

Hanina, M. Journal of Swimming Research (16) 11-17

Lyndon, H. (1989). I did it my way! An introduction to “old way / new way” methodology. Australasian Journal of Special Education 13:32-37

Yarrow, K., Brown, P., & Krakauer, J.W. (2009). Inside the brain of an elite athlete: the neural processes that support high achievement in sports. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10: 585–596